The Traitor of Sherwood Forest

A conversation with Amy S. Kaufman about her dazzling new Robin Hood retelling, including a medieval recipe for conserves

Happy Beltane—

It’s the end of spring: ants, ants, and more ants. Bees bumbling from wildflower to wildflower. I’m fighting weeds in the garden. My baby blackberry bushes are stretching up toward the sun along my backyard fence. Here in Atlanta, there is reliable heat, finally, eighty degree weather. Hopefully, there is change in the air, too. This season, I’m desperately wishing you all—and the whole world, really—a return to the light.

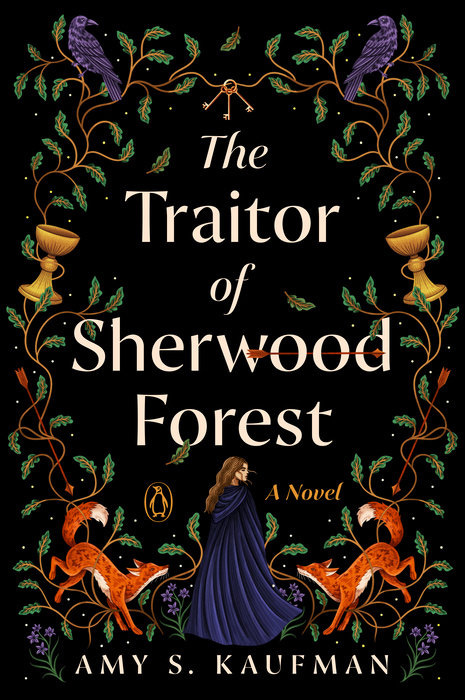

Continuing my series on retellings of classic stories, this year, I’m excited to tell you about a new retelling that came out this week, which I was lucky enough to read in advance. Amy S. Kaufman’s debut, The Traitor of Sherwood Forest, reimagines the story behind the legend of Robin Hood in the 13th century from the perspective of a medieval peasant woman. It’s a novel about, as Kaufman herself wrote, “finding power, especially when you don’t think you have any,” a theme that really resonates with me right now.

You all know how much I love folklore and medieval history, and this book is such a dazzling tapestry that weaves both together. Kaufman is a literal medievalist, and she delivers a Sherwood Forest so real, so full of light and shadows and nuanced characters, you can’t help but wonder if this is what really happened. I mean, look at the way she describes Robin:

Robin came into view right as he was gesturing grandly, his eyes bright with fire, sitting with one leg up on a log as though it were a woodland throne. He had fox-colored hair, just as Bran had said, and his eyes flashed as green as new growth in the forest.

And here is one of my favorite descriptions, although there are honestly so many like this, it was hard to choose. Every description is like this, detailed, intensely visual, and so immersive you’re swept away in the world:

The little pocket in the forest was a shrine. A portrait of the Virgin stood on a tree stump. It must have been taken from one of the churches—one of the nice ones. Gilt framed Mary’s face, her eyes sapphire, her skin bronze like an old coin. Scattered around the stump that served as her altar were endless small treasures: seashells, crusted with salt; a gem-studded drinking horn filched from a lord; arrowheads, one tinged dark brown at the tip; rosaries and brooches with beads that sparkled even in the dim forest shade.

On every page, you feel like you’re there, walking through those fabled woods, and this book is a page-turner too: sultry, suspenseful. But that’s enough from me—let’s turn now to Amy S. Kaufman, who was kind enough to answer my questions about this beautiful book!

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and conciseness.

MM: One of the most striking things about this novel is your portrayal of Robin Hood, which is different from the way he is usually portrayed. He’s charismatic, yes, clever, yes, but your Robin is also selfish and dangerous. He’s a hell of a love interest. You’ve written elsewhere about how the legend of Robin Hood has changed over time. Can you talk about what inspired you to portray Robin as you did? Were you trying to extrapolate what might’ve been before his first mention, or did you have another, perhaps more modern inspiration?

ASK: If you dive into any of the pre-1500 Robin Hood ballads, you’ll find that the charismatic, selfish, and dangerous Robin Hood is right there! From the first time I discovered how dramatically different he was from the Disney fox I grew up with, I was deeply curious about his appeal—because he is appealing. Even though he’s not the morally righteous Robin Hood we love today, medieval people really did go wild for him.

I feel like the class difference between the medieval Robin Hood and the modern one is important to understanding his popularity. Our modern Robin Hood is a disinherited noble who swoops in to save the poor and oppressed, which sends a very different message from the flawed medieval Robin Hood, who has no social standing, and whose goal is to disrupt power and stick his finger in the eye of authority. I can’t help but think that the reason medieval people adored their version of Robin Hood is not that they thought he would rescue them, but that they saw themselves in him. The Robin Hood ballads, as strange and violent as they could sometimes be, were a way people had of imagining their own agency against forces that seemed too powerful and impenetrable to disrupt in real life.

I wanted to explore what made the medieval Robin Hood tick, what provoked him to act, if it wasn’t out of altruism (or the desire to get his property back). The historical moment I set his story in helped me build his background. My Robin is someone who feels betrayed by the leaders who sent him to war for their own greed. He’s a man of deep faith who has seen the church turn to avarice and tyranny. He’s looking for justice, but he knows the ruling class is only interested in preserving its power. Obviously, there are parallels to the present day in his story, and it wasn’t too hard to tap into the anger and frustration he might have felt, or the way he would be torn between idealism and cynicism.

MM: Another thing I love about this book is how real the world feels. Before I read this book, Sherwood Forest felt hazy to me, like it couldn’t possibly exist as a real place—and Robin and his men felt like two dimensional characters who had stepped out of a fairy tale. But in this book, I feel like I’m transported to a place in history with complex characters who could’ve actually existed. I know you have a background in medieval history, and that you drew heavily on medieval sources to create this world and story. Can you talk about the sources you drew from to create this story—both legendary and historical—and how you used them to rewrite the legend? Who was your inspiration for Jane?

ASK: I am so incredibly glad that the world and characters of Sherwood Forest feel real to you! They feel real to me too—although I have spent a lot of time with them! Starting from the position of a flawed Robin Hood helped me think through other characters and their motivations with more depth. If Robin wasn’t some perfect hero, then that gives the Sheriff of Nottingham potential reasons to be against him and still think he’s doing the right thing, for example.

My sources were really varied, but I tried to stay close to the medieval ballads most of all, which are collected in Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. I also wanted to understand a peasant’s lived experience for Jane—and a kitchen girl’s! Bridget Ann Henisch’s Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society is full of excerpts from medieval sources and gave me a really good sense of how people cooked and ate and celebrated, and how utterly sick of fish they were during Lent. Barbara Hanawalt’s The Ties that Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England was also really useful. Both of those sources record life a little later in medieval history than I was writing, so I had to dig backwards for some of the finer details, but they were great starting points.

As for Jane herself, I found her between the ballad lines. Medieval literature is full of gaps: anonymous people who appear and disappear—especially women—and story arcs that are dropped or don’t make sense. In the poem “Robin Hood and The Potter,” Robin pretends to be a cookware merchant as a ruse to get inside the sheriff’s house. In one scene, an anonymous girl appears and carries Robin’s pots to the house, and then she’s never mentioned again. Jane was already living in my head by then because I knew I wanted to write Traitor from a woman’s point of view, so rereading “Robin Hood and The Potter” made it all click together for me. This is how Jane would exist in Robin’s world: quietly and anonymously, invisible to all the important people, her name lost to history.

MM: Did you do a lot of research into medieval cooking and baking, like I did for Gothel? Are there any recipes from the book that you could share? I’m super into historical baking and cooking, and I often hear from readers about trying or wanting to try historical recipes…

ASK: Looking for a good recipe to share—as opposed to something like eels in herbolace—has made me realize just how many things Jane hates cooking, but I guess that comes with cooking for a living…

Fruit was precious in medieval England, so I did a lot of research into which fruits and berries would be available in the thirteenth-century, and the way a peasant might preserve it without access to sugar, modern cans or jars, gelatin, or other kinds of common preservatives. Unfortunately, there are no measurements available in medieval recipes, so I’ve adapted this from a cranberry sauce I make for the holidays.

Jane’s Warden Conserves

This will make a condiment similar to a chutney that you can store in the fridge and eat within a few days, but if you’re into canning and jarring, it should also keep well.

5 cups pears, sliced and cored. (Warden pears are hard to come by nowadays, so any good baking pear will do.)

1 cup rowan berries. (Cranberries could be a replacement)

1 cup honey

1 cup sweet wine

1 cup water

Ingredients that Jane wouldn’t have at home but will make your life easier:

1 orange, peeled and chopped, membrane removed

1 T apple cider vinegar

1 T ground ginger

2 cinnamon sticks (remove after cooking)

Combine all the ingredients in a sauce pan and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer until soft and fragrant (at least 30 minutes). You can add a little water at a time if it starts to dry out before the pears and berries are soft.

Rowan berries are bitter, so if you prefer things sweeter, you can add sugar, chopped dates, or more honey to taste. In The Traitor of Sherwood Forest, Jane cleverly adds flower petals to her conserves for flavor—a common trick documented in royal kitchens, if not peasant ones, so you could add violet syrup to this recipe to make it sweeter, but still keep the flavors of Jane’s conserves. I would leave out the ginger if you add the violets…

Violets! That sounds so lovely. Thank you so much for taking the time to answer these questions, Amy. This novel is truly a breathtaking read, especially if you grew up loving the Robin Hood story and want to come back to it as an adult and see it manifested as something that feels true.

If you’re a medieval folklore fan, the novel is out now anywhere books are sold, or you can order it directly from the publisher here! If you read it, let me know what you think!

I won’t send another newsletter out for a while, but the next time I do, I’ll be talking with author Louisa Morgan (A Secret History of Witches) about re-enchantment and melding magic and history in fiction, as well as her upcoming Arthurian retelling, The Faerie Morgana! Stay tuned…

Sounds like a must-read!

Oh, I am SO there for this! 🌳